Trap-lining vs Central-place Foraging Illustration

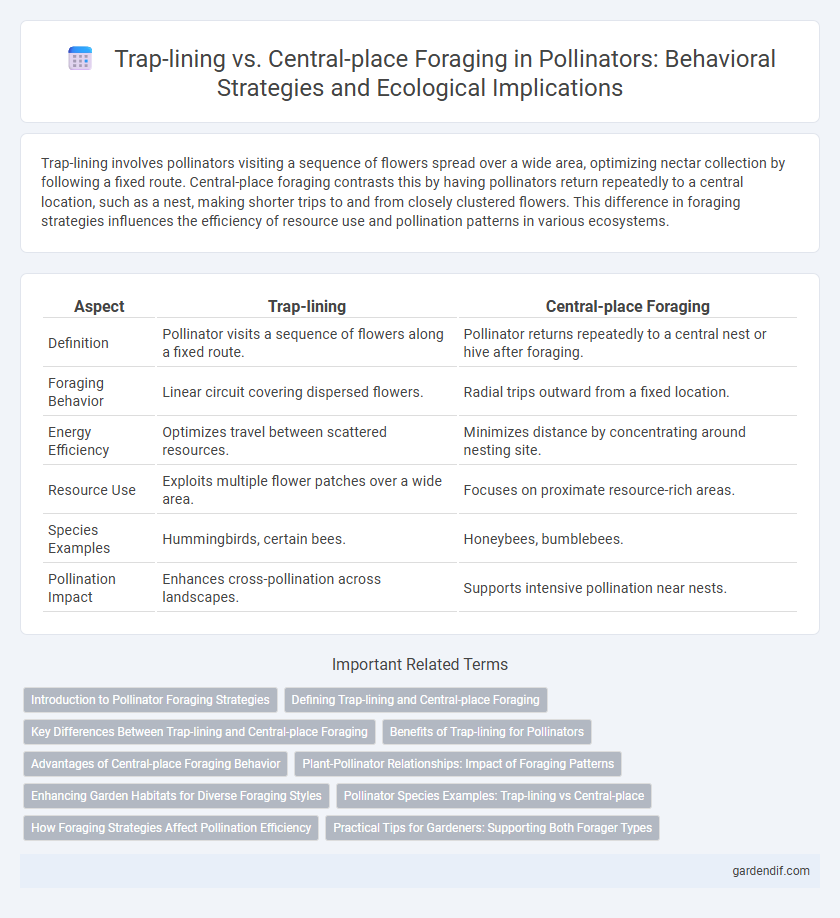

Trap-lining involves pollinators visiting a sequence of flowers spread over a wide area, optimizing nectar collection by following a fixed route. Central-place foraging contrasts this by having pollinators return repeatedly to a central location, such as a nest, making shorter trips to and from closely clustered flowers. This difference in foraging strategies influences the efficiency of resource use and pollination patterns in various ecosystems.

Table of Comparison

| Aspect | Trap-lining | Central-place Foraging |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Pollinator visits a sequence of flowers along a fixed route. | Pollinator returns repeatedly to a central nest or hive after foraging. |

| Foraging Behavior | Linear circuit covering dispersed flowers. | Radial trips outward from a fixed location. |

| Energy Efficiency | Optimizes travel between scattered resources. | Minimizes distance by concentrating around nesting site. |

| Resource Use | Exploits multiple flower patches over a wide area. | Focuses on proximate resource-rich areas. |

| Species Examples | Hummingbirds, certain bees. | Honeybees, bumblebees. |

| Pollination Impact | Enhances cross-pollination across landscapes. | Supports intensive pollination near nests. |

Introduction to Pollinator Foraging Strategies

Pollinator foraging strategies primarily include trap-lining and central-place foraging, each representing distinct ecological behaviors for resource collection. Trap-lining involves pollinators visiting a fixed sequence of flowers spread over a large area, optimizing nectar and pollen intake with minimal energy expenditure. In contrast, central-place foraging sees pollinators repeatedly returning to a central nest or hive, focusing on resource patches near the home base to efficiently support colony needs.

Defining Trap-lining and Central-place Foraging

Trap-lining describes a foraging strategy where pollinators visit a sequence of specific flowers or plants in a repeated, predictable route to efficiently collect nectar or pollen. Central-place foraging involves pollinators returning to a fixed nest or hive location after each foraging trip, optimizing the transport of resources back to the colony. Both strategies influence pollination patterns and the distribution of floral resources within ecosystems.

Key Differences Between Trap-lining and Central-place Foraging

Trap-lining involves pollinators visiting a sequence of dispersed floral resources in a predictable circuit, optimizing energy expenditure over a wide area. Central-place foraging centers around a fixed nest or hive, with pollinators repeatedly collecting resources nearby to efficiently transport them back to the colony. The primary difference lies in spatial movement patterns: trap-lining covers extensive, non-repetitive routes, while central-place foraging concentrates on a localized resource cluster for sustained collection.

Benefits of Trap-lining for Pollinators

Trap-lining enables pollinators to efficiently exploit widely dispersed floral resources by establishing stable, repeatable routes that minimize energy expenditure. This foraging strategy enhances resource predictability and nectar replenishment rates, supporting sustained energy intake over time. By reducing competition at individual flowers, trap-lining fosters pollinator coexistence and promotes overall ecosystem pollination services.

Advantages of Central-place Foraging Behavior

Central-place foraging offers pollinators the advantage of efficiently transporting nectar and pollen back to a fixed nest, minimizing energy expenditure during repeated trips. This behavior enhances resource defense and enables better optimization of foraging routes, increasing overall reproductive success. By centralizing food storage, pollinators improve colony growth and resilience in fluctuating floral environments.

Plant-Pollinator Relationships: Impact of Foraging Patterns

Trap-lining foraging involves pollinators visiting a sequence of flowers spread across a landscape, enhancing cross-pollination and genetic diversity among plant populations. Central-place foraging, where pollinators repeatedly visit flowers near a fixed nest or hive, often results in intensive pollination of localized plants, promoting consistent seed set but potentially reducing genetic variability. These distinct foraging patterns critically influence plant reproductive success, floral trait evolution, and ecosystem resilience in pollinator-dependent environments.

Enhancing Garden Habitats for Diverse Foraging Styles

Trap-lining pollinators follow consistent, circuitous routes visiting scattered floral resources, while central-place foragers repeatedly return to a fixed nest or hive. Designing garden habitats with a mix of spatially distributed flowers and clustered plantings supports both foraging strategies, promoting biodiversity and pollination efficiency. Incorporating native plants with staggered bloom times ensures continuous nectar and pollen availability, catering to diverse pollinator needs throughout the growing season.

Pollinator Species Examples: Trap-lining vs Central-place

Trap-lining pollinators, such as hummingbirds and certain butterfly species like the pipevine swallowtail, follow a repeated circuit visiting scattered floral resources, optimizing nectar intake over wide areas. Central-place foragers like honeybees and bumblebees collect nectar and pollen by repeatedly returning to a fixed nest or hive, maximizing resource transport efficiency within a localized foraging range. These distinct foraging strategies reflect adaptations in pollinator behavior and ecology critical for plant-pollinator network dynamics and biodiversity maintenance.

How Foraging Strategies Affect Pollination Efficiency

Trap-lining pollinators follow consistent routes visiting resources in a sequential pattern, which enhances pollen dispersal over wider areas but may reduce visit frequency per flower. Central-place foragers repeatedly return to a fixed nest location, concentrating visits on nearby flowers and increasing pollination efficiency through higher visitation rates. The balance between these strategies influences plant reproductive success by optimizing pollen transfer dynamics based on spatial resource distribution.

Practical Tips for Gardeners: Supporting Both Forager Types

Trap-lining pollinators, such as certain hummingbirds and bees, follow fixed routes between flowers, requiring gardeners to plant a variety of nectar-rich plants spaced evenly to support their foraging patterns. Central-place foragers like honeybees rely on a concentrated area with abundant floral resources near their nests, so clustering native flowering plants in dense patches ensures efficient energy use. Creating a diverse garden habitat with both spaced-out blooms and dense floral clusters maximizes pollination by accommodating the needs of both trap-lining and central-place foragers.

Trap-lining vs Central-place Foraging Infographic

gardendif.com

gardendif.com